Join us for 40 Days of Prayer for the Miao-Hmong

For more than 4000 years, the Miao have lived in fear of evil spirits. Many of their languages are unwritten with no Bible or Christian witness.

Who will share God’s love with them? How will the Word be translated into their languages?

God is God. He can do anything He wants anytime. But He most often waits until we pray. He wants to partner together with His people to see the Miao worship Him, to be His army of Light, pushing back the darkness so the lost can see Him and His church can grow and thrive.

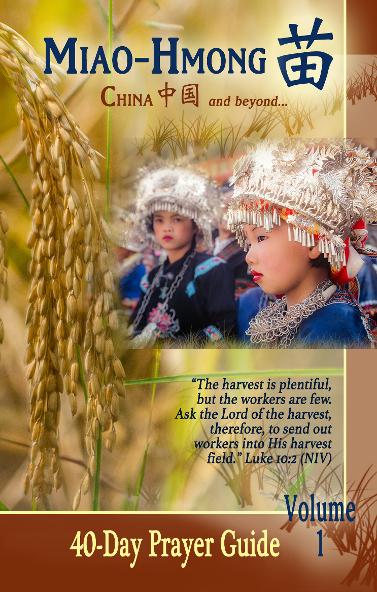

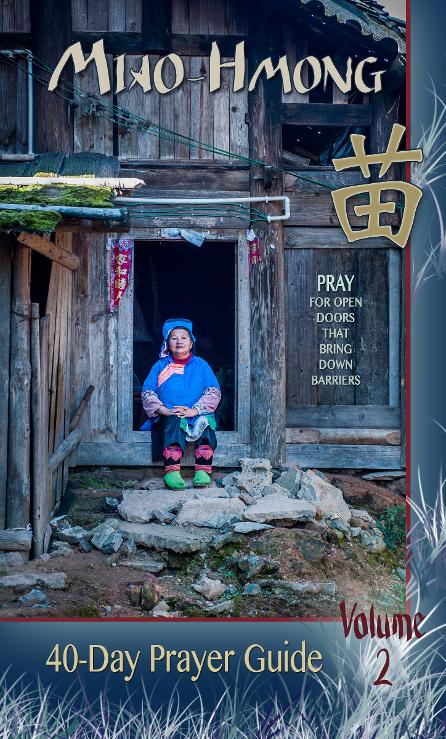

Volume Two is now available!

This full-color booklet with striking photos of Miao people and landscape is small enough to travel with and beautiful enough to lay on your coffee table. Order at cost, add a donation to help with Miao-Hmong work, or ask for a free pdf by writing MiaoUPG@gmail.com.

Volume One introduces all four main Miao groups, and the many languages that fall within those groups, including those which have no witness at all. Prayer starters for each day pull you into powerful times of asking God to draw all Miao peoples to Himself.

Volume Two describes barriers and troubles the Miao face, and offers prayer starters to bring down those walls so they can be saved and churches can grow.

Order Volume Two for yourself, your church staff, prayer group, church members, or as unique gifts for those who long for the nations to know Christ.

Only the PDF is available at this time for Volume One.

Miao Quick Facts

- 12 million world-wide

- Trapped by persecuting governments

- Isolated by high mountains

- More than 80 languages

- Only 3 languages with a Bible

- Poor, oppressed

- Despised by those unlike them

- Friendly and hospitable

- Animistic, venerating spirits

- Devoted to family

- Lovers of music, dance, and art

- Agriculturalists

THE MIAO-HMONG peoples number more than 12 million world-wide and speak more than 80 different languages, many of which are so diverse that they cannot understand each other from one village to the next.

Spread throughout Southwest China, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, and several other countries like the USA, Argentina, and France, where thousands took refuge after the Vietnam War, the Miao are known for their extravagant silver jewelry, intricately embroidered clothing, and unique music.

Although nearly all of the Miao-Hmong groups are related, they distinguish themselves by their varying dialects, clothing styles, and names. "Hmong" is a common term the Miao call themselves in several of their dialects and languages. But because other Miao groups do not use that name for themselves (such as the Hmu and the Xong), we will use the Chinese term "Miao" on this website to refer to all Miao-Hmong ethnic and linguistic tribes.

A Miao man plays with his baby in a village in central Guizhou near Guiyang City (above), and a White Hmong man in northern Thailand tends to his shop (top left).

Miao History

The Miao are among the most colorful and ancient people groups in China. During the days of Abraham, when other nationalities in China were living primitively,it is said that the Miao already had a well-developed culture and tribal structure in central China's Yellow River valley. Chi You, their leader, is said to have founded their religion, enacted a sophisticated criminal code, and initiated the use of arms.

However, wars with neighboring tribes ended in the defeat of Chi You. Forced to leave their homes, the Miao moved to the central area of the Yangtze River, and then to the south. Around 200 b.c., during the reign of Shih Hwang Ti who built the Great Wall, the Miao retreated further west into the higher and more barren mountainous regions.

Yet, they still could not escape persecution. Dynastic rulers forced the Miao into subjection century after century. The Qing Dynasty, a 300-year rule of the Manchu minority, was the worst. In 1726, the Qing court forced a replacement of the Miao's hereditary headmen with its own officials. To subdue those in opposition, Qing troops set more than 1000 Miao villages on fire, killed tens of thousands of Miao people, and destroyed their farmlands. In 1795 the Miao of Guizhou and western Hunan took up knives and long pikes in revolt, defeating Qing troops and occupying many townships for as long as 12 years.

Other uprisings ensued, as did slavery. Some of the Miao tribes traveled deeper into Southeast Asia to escape persecution, where they are called Hmong and have become 20th century war refugees, many of which have relocated to the United States and other countries, where they can hear the Gospel freely. Yet their brothers remain isolated in China by a history they cannot control.

This diaspora also led to many languag

Some Miao have blonde or red hair, a trait which set them apart from other oriental tribes and made their villages easy to find by those who sought to extinguish them. Today, the gene still resurfaces in some areas.

History in Embroidered Pictures

Some historical sources say the Miao were already settled in eastern Guizhou by 770-221 b.c. Today, the highest concentration of Miao still remains in that province.

Theirs was a history of rebellion against oppressive rulers. And through the centuries, legends of brave warriors have been recorded.

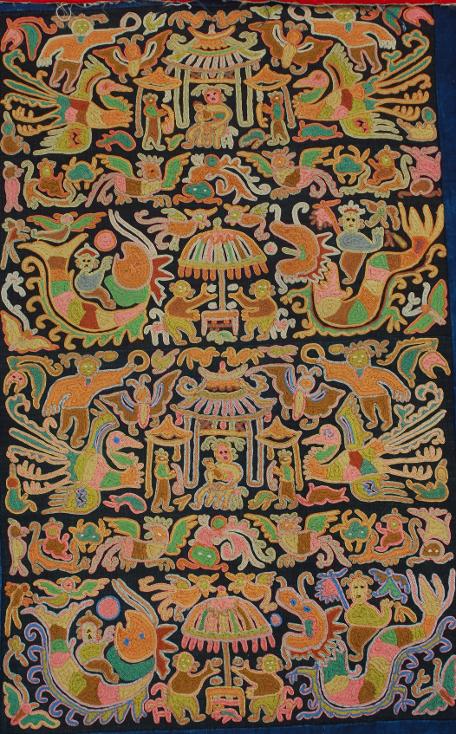

Because the Miao had no writing system, embroidery became an important source for remembering their past. Today, women are taught the techniques of their village from the time they are small children. In fact, expertise in embroidery is often a criteria for a good wife, although this custom is gradually fading as more and more families move from villages to the city to find work.

The styles of embroidery vary from place to place with women using cotton or silk thread in cross-stitch or tight, long stitches, and sometimes even building up the embroidery on top of itself for a three-dimensional effect.

One legendary figure often portrayed through embroidery is a woman named Wu Yaoxi. Born in Shidong, Guizhou, she joined the Miao rebellion against the Qing Dynasty (1855-1872) and became a famous general. All of the rebels eventually paid with their lives, but their heroic deeds have not been forgotten by the Miao people.

A typical embroidered scene might show Wu Yaoxi, umbrella in hand, mounted upon an animal, such as a horse, tiger, or dragon. Chased by the enemy, she opens her umbrella to avoid capture, and simply flies away. Some artists may embroider her image as having wings, and often Mother Butterfly -- whom Miao legend says is the mother of all creation -- hovers nearby, perhaps in watchful care.

It is interesting that so many Miao legendary figures are those who have been defeated by the enemy or who have done wrong deeds of some kind; yet the Miao still remember them through embroidered images for their valor and strength.

(Left) A story cloth depicting several Miao legends in ancient 3-D style embroidery, where the thread is braided. (Below left) Northern Qiandong Miao women from Shidong, Guizhou, embroider together in community.

Animism, Living in the Shadow of Fear

A Miao man sacrifices a chicken.

Short History of Missions for the Miao of China*

The first Protestant mission efforts in Guizhou began in 1877, but it was not until 1886 that China Inland Mission (CIM) first went into a Miao area. Samuel Clarke made contact with a Hmu (Miao from SE Guizhou) believer in Guiyang from Panghai in 1895, and in 1896 he moved to Panghai. Although the missionaries met much opposition, the missionaries used to their advantage the unequal treaties of 1842 and 1858. They said “We told them that we were there by treaty right; we had our passports, the high provincial authorities knew we were there, as did the local magistrates at Tsingpinghsien, and we intended to stay.” The Boxer Rebellion of 1900 disrupted the missionary work all over China. Its disastrous results were foreshadowed in 1899 when William Fleming of the CIM and Pan Xiushan, the first Miao convert, were murdered in Chong’anjiang (Left photo: missionary William Fleming's grave in Southeast Guizhou). Apparently Pan was suspected of importing arms to support another Miao uprising. Mission work in SE Guizhou went slowly, at times having people respond, and when the missionaries returned from furlough, they often found that many of the converts had fallen away and gone back into their animistic practices. It is calculated that in 1949 when the missionaries left that area there were around 200 Hmu belivers. Of the 2 million Hmu in SE Guizhou today, an estimated 1000 confess Christ.

The real harvest in Guizhou came under the ministry of J.R. Adam of CIM in the area around Anshun near Guiyang City. Adam opened the first chapel and a small boys school for the Flowery Miao in 1899, but his work attracted Chinese as well as their minority neighbors. He worked with both groups until 1900, as inquirers came from 250 hamlets and villages in the surrounding area. When the Boxer turmoil erupted, he and his colleagues were in great danger. The Empress Dowager had issued an edict to all provinces to kill the foreigners. The viceroy in Guizhou not only disobeyed this order, he sent an escort to accompany missionaries fleeing for refuge to Shanghai. Following this chaotic period, Adam was not certain whether anything would remain of this incipient movement. Particularly was he fearful when he learned that a military official and a noted village headman had gone throughout the entire district, threatening with death any who would opt for this foreign religion. Some of his fears were justified. Only 20 chose to be baptized at his first baptismal service in 1902. But a network of villages had been established, and the Gospel carried rapidly by the people themselves into many villages of the Flowery Miao. In a very short time, hundreds of them had believed in Jesus and were willing to follow Him. Adam, B. Curtis Waters, and others of their colleagues baptized many of these new converts, organized them into churches, and mobilized them to reach into the many villages where the Christian message had not yet come. By 1907 the missionaries could speak of 1200 communicants. In all, Adam personally baptized approximately 7000 Miao during his ministry.

One thing that troubled Adam was that obviously many who came to him had traveled a great distance, some from Zhaotong in Yunnan Province three days distance on foot. He urged them to visit Samual Pollard, the Methodist missionary in charge of Chinese work. They were not sure about Pollard since they had not met him, but they were willing to give him a chance, and the miracle of mass turning to Christ happened again. At first, a few Miao showed up at Pollard’s door to hear about Jesus, but soon 200 were coming for teaching. Pollard’s first trip to the Miao's mountain homes was in 1904. He preached, taught, baptized converts, and organized them into churches, but found Zhaotong too far away for effective ministry. One of the leading chiefs gave him a plot of land across the border in Guizhou where he erected a chapel, a home, and educational facilities for all facets of the Miao work. This site, known as Shimenkan (Stone Gate) became the center of all Methodist Miao work. Three other subsidiary centers were developed, and from these radiated outward a network of sites for the development of the work. Within three years, more than 1000 converts had been baptized.

Soon after this, two Miao lepers went to see Pollard hoping to be cured of their leprosy. They learned that Jesus could heal them from their sin and returned joyfully to tell their fellow villages about this new message. They soon requested that Pollard send a missionary to their villages. Overwhelmed by his expanding ministry, Pollard requested that the CIM assign one of their missionaries to this new work. Its leaders sent Arthur Nicholls, then stationed in Kunming, to go to Sapushan in the eastern part of Wuding county. Nicholls studied under Pollard for a time and learned about Miao ministry before heading to his new assignment, and very shortly he had established chapels in five areas, and the work gained the same momentum as it had shown in Anshun and Shimenkan. Whole villages turned to Christ from idolatry, witchcraft, debauchery, and various levels of drug addiction. Freed from these oppressive burdens, their economic picture brightened and their lives and societies took on a new dignity. In 1932, the CIM estimated that the Miao church in the Wuding area numbered about two thousand with several thousand more in the wider Christian community. Today, the Big Flowery Miao number around 350,000. Approximately 70% of these are professing believers.

Big Flowery Miao church, China

Big Flowery Miao Bible

Big Flowery Miao young people sing

*Covell, Ralph. The Liberating Gospel of China. Pp. 83-93.